I arrived back in Beijing after three and a half weeks away, across oceans in America and then straits in Taiwan. While on vacation, I reminded myself constantly that even though the air is sometimes lousy and traffic unceasingly loud, Beijing is the center of the Chinese Xiangsheng Comedy world—the heartland of the comedy style I have come to love so much. I was excited to get back into the Xiangsheng scene.

And a mere nine hours after landing in Beijing, that’s exactly what I got the chance to do.

I arrived at the Wu Lin Feng Teahouse Thursday afternoon to find my troupe hanging around a giant ornate wooden tea table the size of a refrigerator lain on its side. Master Ding and several of his students were already there, and soon we were laughing and catching up. Master Ding’s fantastic energy pervaded the entire teahouse; even the wait staff were grinning ear to ear as they stood by the cash register, waiting for us to sit down.

The purpose of the day’s meeting was to discuss tea culture for an article being written by the China Tea Expert Weekly magazine. They had invited Master Ding and his students, assuming that a comedian would produce an interesting piece with little prodding on their part. Digging into his life-time bank of experience, Master Ding had brought with him a Xiangsheng piece about tea culture that he had written with a student of his several years ago. “There’s a rap in there that I wrote about tea,” he told me, handing me the script. “Find it and get ready to rap for us later.”

Master Ding and Mr. Ye, the head of Wu Lin Feng, told us about the varying aspects of tea culture. According to Master Ding, a cultured person must know three things: 茶,文,酒 (Cha, Wen, and Jiu) or Tea, Art, and Liquor. Mr. Ye told us that in ancient times, the word Cha, or tea, was used for anything potable; nowadays, only certain types of teas counted as real tea, including teas like green tea, red tea, and oolong tea, but excluding items like 面茶 (Mian Cha), a type of mushy porridge made from millet whose “Cha” character is a leftover remnant from the old usage of the word.

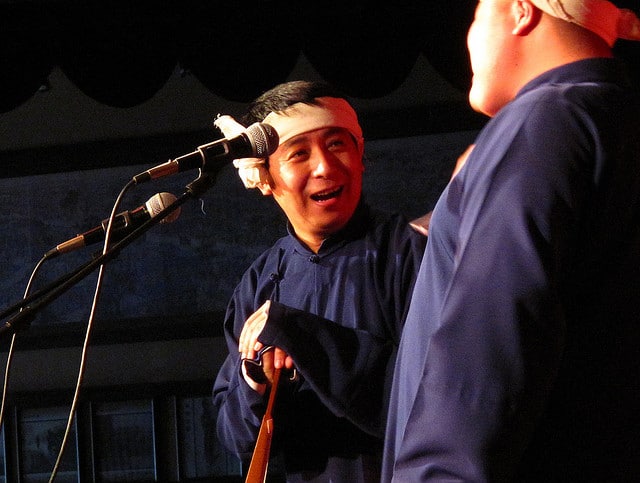

Our conversations about tea would often be broken up with bits of Xiangsheng. For twenty minutes at a time, some of the Xiangsheng students would stand up, at the behest of the reporters or Master Ding, and perform a piece they’d been rehearsing.

Sipping high mountain tea from Fujian and laughing at the zany back-and-forth of a Xiangsheng piece is about as good as it gets for me. I could see why Xiangsheng is performed in teahouses; the environment was perfect for jokes; the room, small and intimate.

Two of Master Ding’s Chinese students performed a piece about riddles.

“Cui Laoshi is very smart,” Guo Yufeng, a young Chinese student of Master Ding’s.

Cui Laoshi, a sixty-five year old student of Master Ding’s, waved his hand. “No, no,” he demurred.

“If you don’t believe me,” Yufeng told the audience, “We can open up his head and look.”

Cui Laoshi fought off Yufeng’s hands as they clawed at his skull. “How come everything always ends up with you trying to kill me?”

As the audience laughed, Yufeng pulled back his arms. “Well, we can prove smarts another way. How about a riddle? See if you can get this one. Ten birds are alighted on a tree. You take a gun and shoot one of them. How many living birds are left on the tree afterwards?”

Cui Laoshi furrowed his brow in confusion. “Well, there’s got to be nine, right?

“Wrong!” Yufeng said.

“How am I wrong?” Cui Laoshi asked. “Ten minus one is nine!”

“After one bird gets shot, you think the others will stick around? They’re all gone after the shot, flown away!”

With tea and art taken care of, all that was left was a huge dinner courtesy of Mr. Ye complete with wine and baijiu to round off the cultural triumvirate. As we discussed everything from immigration law to patriotic songs at the dinner table, we laughed our heads off, bonding over the common link of humor. Memorizing scripts is hard, and understanding the culture behind them is even harder, but when we share laughter with each other even the hard work seems like fun.

My job as a performer, one who straddles cultures with each performance, is to find a way to take this feeling and spread it to everyone—Chinese and non-Chinese alike.