Hello,

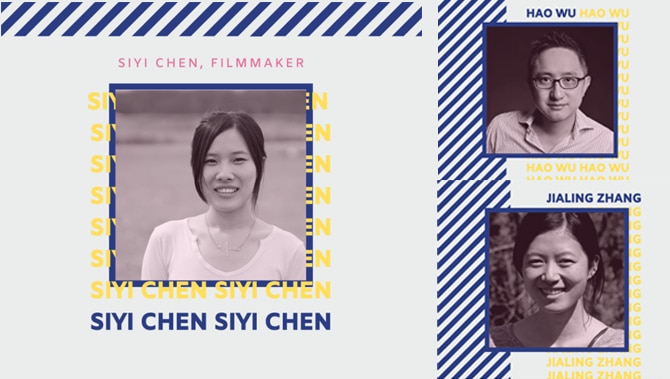

I’m Siyi Chen, an independent documentary filmmaker based in China and the US. Born and raised in Zhejiang, educated in New York, it is a natural choice for me to constantly move across borders for a documentary career in both countries.

A growing number of filmmakers like me are taking advantage of their access to multiple cultures, making never-seen-before films about China for the international audience or using their international experience to help develop a nascent documentary industry back home. There are enough of us to form a WeChat group called the “Chinese Doc Mafia.”

Some of us made films nominated for the Academy Award; others directed films that challenged stereotypes and achieved tangible social impact. We bump into each other at filmmaker panels, fundraising forums and prestigious film festivals across the globe.

While the future is exciting, Chinese filmmakers like me also face many challenges. We’re constantly asked by investors: “Can your documentary serve both Chinese and international audiences? “Or, “how do you deal with the ever worsening censorship of the Chinese documentary industry? What about the risks you bring to your characters and yourself? How can a film that cannot be watched in China achieve impact there?” Questions like these often discourage international co-productions and funders from providing essential support to our work.

We also often face questions from the Chinese audience: “Are you sensationalizing and stereotyping our stories for the world?” While nationalism plays a role in these doubts, we still have to ask ourselves: is there any truth to this argument? How do we challenge stereotypes with our work?

For this special edition of the Chinese Storytellers newsletter, we invite my fellow Chinese documentary filmmakers to discuss the opportunities and challenges of making films that cross geographical and cultural boundaries.

Thank you,

Siyi Chen

P.S. Don’t forget to RSVP to our upcoming event: a conversation with filmmaker Hao Wu about his film “76Days” on the COVID-19 outbreak in Wuhan. Friday, October 30, at 9 p.m. EST. Register HERE. Attend a free screening of the film here.

What are some of the pros and cons of making documentaries about China from abroad?

Hao Wu, Director, Producer – “76 Days,” “All in My Family”, “People’s Republic of Desire”

The biggest advantage is the freedom to pick any topic you’d like to pursue and just do it. You wouldn’t worry about potential censorship. In the past, there used to also be the advantage of working in an environment where the nonfiction media market was more mature, so you could follow certain paths to have your documentaries funded, screened at film festivals and then distributed commercially. But this advantage is fast disappearing as China’s documentary market develops. The biggest disadvantage is the distance between the films and the most receptive audiences. Documentaries, as news and other non-fiction media, should be part of a society’s discussions about culture, social issues and political concerns. Yet documentaries about China produced overseas, on topics that may invite censorship, rarely find wide distribution in that country, thus limiting their impact.

For example, my Netflix doc short “All in My Family” is finding resonance among Asian American communities and many other developing countries where the LGBTQ rights movement encounters resistance from traditional forces. I’d love to have that film widely distributed in China, where it would stimulate the most discussions given the film’s cultural and linguistic roots. But as we all know, China is increasingly prohibiting LGBTQ presence in the media. My previous feature documentary, “People’s Republic of Desire,” suffered a similar fate. Despite the absence of any overt political message, the film could not get past the censors. For a film about live streaming, an internet craze that finds its most eager adoption in China, not being able to publicly screen in China is a real shame.

Jialing Zhang, Director, “One Child Nation,” “Complicit”

Instead of focusing on what international audiences might be interested in, I tend to focus more on what I want to express and what interests me. Every film would find its audience ultimately if it’s convincing and can provoke thinking and emotions. Last year, I saw at many international film festivals that audiences are interested in all kinds of China-related films – some very personal, some political, and some experimental. Although documentaries focusing on China’s social issues usually require more clarity and context, I think cinema is an international language and art form: as long as the director is able to evoke universal emotions through storytelling, they can find their own “international audience.”

Regarding stereotypes, sometimes I would do research to see whether there have been some common preconceptions the audience may hold. If there are, I would try to acknowledge and challenge those biases. I would also look into popular documentaries on the same issue and think about why I want to make another film about the topic and how mine could provide a different perspective. If the film just repeats points that had been made, I would reconsider if I want to make the film. I’ve seen films that reinforce propaganda or omit facts to get around China’s censorship. This makes me think about why I want to be a filmmaker in the first place. There is only one truth, but many interpretations of realities. What’s important for me as a filmmaker is the ability and willingness to do thorough research, be truthful and fight for what we believe is right.

(Note: Excerpts of Siyi Chen, Hao Wu and Jialing Zhang’s blogs are published with permission from The Chinese Storytellers. For more – click here.) [:zh]Hello,

I’m Siyi Chen, an independent documentary filmmaker based in China and the US. Born and raised in Zhejiang, educated in New York, it is a natural choice for me to constantly move across borders for a documentary career in both countries.

A growing number of filmmakers like me are taking advantage of their access to multiple cultures, making never-seen-before films about China for the international audience or using their international experience to help develop a nascent documentary industry back home. There are enough of us to form a WeChat group called the “Chinese Doc Mafia.”

Some of us made films nominated for the Academy Award; others directed films that challenged stereotypes and achieved tangible social impact. We bump into each other at filmmaker panels, fundraising forums and prestigious film festivals across the globe.

While the future is exciting, Chinese filmmakers like me also face many challenges. We’re constantly asked by investors: “Can your documentary serve both Chinese and international audiences? “Or, “how do you deal with the ever worsening censorship of the Chinese documentary industry? What about the risks you bring to your characters and yourself? How can a film that cannot be watched in China achieve impact there?” Questions like these often discourage international co-productions and funders from providing essential support to our work.

We also often face questions from the Chinese audience: “Are you sensationalizing and stereotyping our stories for the world?” While nationalism plays a role in these doubts, we still have to ask ourselves: is there any truth to this argument? How do we challenge stereotypes with our work?

For this special edition of the Chinese Storytellers newsletter, we invite my fellow Chinese documentary filmmakers to discuss the opportunities and challenges of making films that cross geographical and cultural boundaries.

Thank you,

Siyi Chen

P.S. Don’t forget to RSVP to our upcoming event: a conversation with filmmaker Hao Wu about his film “76Days” on the COVID-19 outbreak in Wuhan. Friday, October 30, at 9 p.m. EST. Register HERE. Attend a free screening of the film here.

What are some of the pros and cons of making documentaries about China from abroad?

Hao Wu, Director, Producer – “76 Days,” “All in My Family”, “People’s Republic of Desire”

The biggest advantage is the freedom to pick any topic you’d like to pursue and just do it. You wouldn’t worry about potential censorship. In the past, there used to also be the advantage of working in an environment where the nonfiction media market was more mature, so you could follow certain paths to have your documentaries funded, screened at film festivals and then distributed commercially. But this advantage is fast disappearing as China’s documentary market develops. The biggest disadvantage is the distance between the films and the most receptive audiences. Documentaries, as news and other non-fiction media, should be part of a society’s discussions about culture, social issues and political concerns. Yet documentaries about China produced overseas, on topics that may invite censorship, rarely find wide distribution in that country, thus limiting their impact.

For example, my Netflix doc short “All in My Family” is finding resonance among Asian American communities and many other developing countries where the LGBTQ rights movement encounters resistance from traditional forces. I’d love to have that film widely distributed in China, where it would stimulate the most discussions given the film’s cultural and linguistic roots. But as we all know, China is increasingly prohibiting LGBTQ presence in the media. My previous feature documentary, “People’s Republic of Desire,” suffered a similar fate. Despite the absence of any overt political message, the film could not get past the censors. For a film about live streaming, an internet craze that finds its most eager adoption in China, not being able to publicly screen in China is a real shame.

Jenny Jiayan Shi, Director – “Finding Yingying”

I’m very interested in social issues. If we take distribution in China out of the picture, there’s a lot of freedom to what topics I can work on from overseas. But the challenges are about how we fund our films and how to tell China’s stories well to an international audience. Funding is an extremely difficult task for most independent filmmakers, and overseas fundraising for stories about China makes it even more difficult. Although my film “Finding Yingying” is a story that took place in the U.S., as I applied for government fundings in the States, the feedback I received was often that the film is “not American enough.”

I had to rely on equity investment and donations from the Chinese American community to finish my film.