“We are so caught up in the myths of the best and the brightest and the self-made that we think outliers spring naturally from the earth. We look at the young Bill Gates and marvel that our world allowed that thirteen-year-old to become a fabulously successful entrepreneur. But that’s the wrong lesson. Our world only allowed one thirteen-year-old unlimited access to a time sharing terminal in 1968. If a million teenagers had been given the same opportunity, how many more Microsofts would we have today?”

This insight is quoted from the bestseller nonfiction Outliers, written by Malcolm Gladwell.

Though I have not read the book—one that is seemingly forever stuck on my to-read list—I read reviews shortly after the book was published in 2008 and am familiar with the premise, one that has largely been accepted by sociologists for decades: a person’s success—historical notoriety, status, and wealth—is strongly tied to that individual’s environment, especially the factors surrounding him or her during formative years. In his own words, Gladwell says in his book:

“I want to convince you that these kinds of personal explanations of success don’t work. People don’t rise from nothing….It is only by asking where they are from that we can unravel the logic behind who succeeds and who doesn’t…We overlook just how large a role we all play–and by ‘we’ I mean society–in determining who makes it and who doesn’t.”

As a person with a sociological research background, the thrust of Outliers aligns with much of what I have read by other social scientists and commentators. But I also relate to Gladwell’s stories on a personal level.

I am not suggesting that I am of “the best and brightest”–though I venture to be the best and smartest version of me.

Rather, Gladwell reminds me of my fortune.

No matter what degree of “success” I achieve from the value perspective of myself or society, it is certain to be more than I would have otherwise achieved without the people and environment with which I have been blessed.

My parents are loving caretakers and successful dentists who provided me with a stable, supportive upbringing. They let me experience so much, a great deal of it based on my own interests and passions.

They modeled (and continue to model) many of the virtues that I consider the best of humanity—generosity, sympathy, work ethic, and humor.

I’m close with a brother who, having grown up under the same roof, has also become a hardworking, high-achieving, and good-humored person.

Add to this a best friend: my strong and loving spouse who has become a partner in life.

Important too was the fine public school I attended, Kenston School District. There I had well-trained teachers, ample resources, encouragement, and opportunities for various extracurricular activities, like student government and athletics.

Chinese people might say that my 条件很好, and they’d be right.

I’ve been extremely fortunate. And any measure of success I obtain will, in no small part, be tied to the opportunities and support afforded to me by my family and my community.

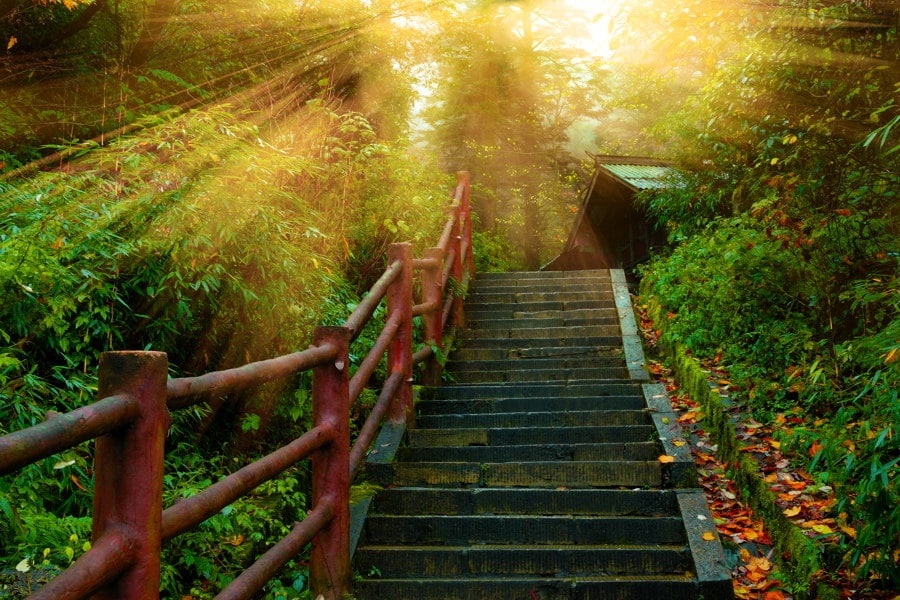

On this foundation, I have the chance to work hard to realize dreams.

And that is something that Gladwell also discusses in his book.

Outliers has become well-known for the 10,ooo-hour rule, which suggests that a person needs to do something for about 10,000 hours to gain a mastery of that activity. This is Gladwell’s way of highlighting that hard work and consistency is also a part of the equation of success. Maybe it’s telling that this part of the story—a concept that promotes the self-made success—is the one most mentioned in public discourse surrounding the book.

But ultimately, Gladwell is arguing that the environment we construct around people will deeply influence their potential:

“To build a better world we need to replace the patchwork of lucky breaks and arbitrary advantages today that determine success –the fortunate birth dates and the happy accidents of history–with a society that provides opportunities for all.”

Looking at the conditions and seemingly insurmountable challenges faced by many people in this world, one should feel great humility to be blessed with a randomly determined birth into a fortuitous place and time.

An excellent way to act on this humility is to pay it forward.

Become a positive participant in society; create an opportunity for someone else that lends them a step up to a place of success.

Because, to quote Malcolm Gladwell once again, “no one—not rock stars, not professional athletes, not software billionaires, and not even geniuses — ever makes it alone.”