In Havana, we saw queues everywhere.

Upon arrival, we joined other foreign adventurers to queue for the only currency exchange outside the Havana airport. To purchase wifi cards, we queued for half an hour with local Cubans in front of the Etesca outlet. And during the entire five days of traveling in Cuba, everywhere we walked — wherever there was a store, there was a queue.

Queues everywhere

Coming from China, a country that has been growing at a rate of 9% for its annual GDP per capita since embracing economic reforms and free-market principles, I am no stranger to how a market economy can be efficient in organizing the production and distribution of goods and generating affluence and prosperity. That being said, I am not an absolute believer in the invisible hands nor is this a treatise against command economy. However, in Cuba, I’ve witnessed how the alternative could reduce consumer’s benefits and result in inefficient resource allocation.

Anyone who has taken Intro to Economics would be familiar with the law of supply and demand. In a free market, when demand increases, price increases, hence providing incentives and signals for suppliers to increase the supply. This would, in turn, decrease the price until the two forces reach an equilibrium.

However, in a planned economy like Cuba’s, either the price or the supply is controlled. In the first case, the price is dictated, hence impacting both supply and demand. When the price is set too low, there is an undersupply hence queues. On the other hand, when the price is set too high, there is oversupply and producers/suppliers actually fight for customers. This was the case of taxis queuing at airports and outside tourist spots, or paladars (private restaurants usually at American price) being empty.

All the taxis waiting

In the second case of supply control, there is quota or legislation that restricts the production or selling of goods and services, which leads to overpriced products when there is a dearth of supply or overproduced goods in the reverse scenario.

One example would be drinking water. Cuba’s water is not directly drinkable. As we could not find any kind of convenience store or supermarket to buy bottled water, we could only get 650ml-bottles at paladares we ate for around 3 Cuban Convertible Pesos (known as CUC, mainly used by tourists), which is 3 dollars.

While it is not rare to get expensive water at restaurants, the water we got was just plain bottled government-produced Cuban water than imported Evian or Perrier. Feeling ripped off, during the first few days, we walked many blocks scouring for bottled water at normal price.

It turned out to be a futile game of cat and mouse. Despite my awkward conversations confronting tourists, police, and waiters, all answers led me to restaurants that sell water at the price.

Perhaps it was just our bad luck for not getting reasonably-priced water, and it is true that many things can be cheap. When we went Vinales, the famous cigar production plantation, we stopped at a small town, and while walking around, I got an ice cream at 3 CUP (0.11 USD) instead of the 2 CUC (2 USD) it might have cost in Havana.

Rare-found 10 cents ice cream outside Havana

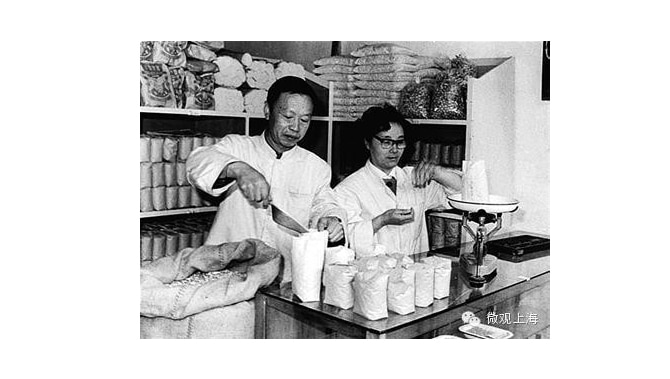

Other negative effects of the command economy include a decrease in consumer choices and the quality of goods and services. When we finally, after many failed attempts, found the (only) so-called supermarket/store of the area, I was reminded of the ration stations I’ve seen in history book or communist-era posters of the old China: in the glass-door locked-up cabinets, a few kinds of goods were displayed with prices in CUC. For every category of goods — confectionary, staples, canned goods etc, only one or two kinds were available, with at most a few dozen of different products in total. Moreover, the supermarket did not sell water.

A depiction of ration station during the 1950s in China

A bodega in Cuba

These state-owned stores/supermarkets (by no means super, at best mini), otherwise known as bodegas, were implemented since 1962 by Fidel Castro as part of the rationing system. Local families would bring “la libreta”, a ration book, which would entitle them to an allotted amount of food per household.

The reasons for the introduction of a system of food rationing are twofold. One, there was an increasing demand for food due to the growing purchasing power. Second, food production decreased as drastic changes were taking place in farm ownership and organization after the 1959 Revolution.

The items subject to quotas have not remained static over time. One example would be eggs. During our stay, we couldn’t even find eggs at the “farmers’ market” where locals buy their fruits and vegetables. When I asked our local day-tour driver, he told me that eggs are rationed right now because, after the Hurricane Irma in September 2017, the production went down.

Examining through the whole bodega, I could not find anything I like or have taken for granted — milk, yogurt, Hershey bars, or chips. The lack of necessities and the dearth of consumer choices instilled within me a sense of urgency and appreciation for what is available never experienced elsewhere. Undaunted, we kept looking for more stores with the faith that there must be some imported goods shops given the number of foreign visitors. Upon the fifth stores visited, I was exhilarated to find a box of long-shelf UHT full-cream milk — one and only one kind — not organic nor fresh, not reduced fat nor lactose-free, down an aisle of uniform preserved fruit. Joining many Cubans for a queue that extended out of the shop, I paid 3 CUC (3 USD) for this rare-found 1L milk.

And it was not just the dearth of consumer goods. Government services can also be lacking. Except for the side near the sea in old Havana, most of the roads and buildings were dilapidated and broken. While they were probably under renovation, they seemed long abandoned. This included the El Capitolio, the National Capitol Building of Cuba, which has been under renovation since 2012, yet was still scaffolded when we visited in 2018.

Capitolio, still scaffolded

Another related consequence of scarcity is the black market, which was abundant in Cuba. Walking on the streets, we were randomly approached by Cubans who would flash out scratch cards, which turned out to be wifi registration cards sold at two times the price for skipping the official queue. Similarly, taxis never run on meters, and everyone seemed prepared to engage in long haggling with you in limited English.

While shortage is common for necessities, there are also many cases of surplus. One example is the bank. We thought we could use CUP for purchases at places locals frequent and get a price advantage, so we went to the bank. (On a side note, CUP, which is the currency locals pay, turned out to be quite useless. We hardly encountered places where both currencies are allowed for foreigners and we would be comfortable to eat or drink, or CUP price would be lower than paying in CUC)

The bank looked stately, yet dismally empty. There were two guards at the door, five idling counters with five assistants, yet the guard told me not to come along with my boyfriend as they could only handle one person at a time.

Inside a bank

Another example was the state-organized tours for foreigners. Originally it was a group tour, but we were the only people who signed up. As a result, it became a private tour. Our driver, who used to be an engineer, was both fluent in English and German and could answer all our questions. However, we also had to have a guide because he had the tourist guide license, though he did not speak much English and knew almost nothing about the places we visited.

On the last night, it was 11 pm when we left the Cabaret concert to go back to our Airbnb in old Havana. Under the dim light, stray cats ran on the puddled uneven road. The old cobbled streets reeked of urine and fermenting trash — until the fragrance of fresh bread eclipsed all the unpleasant.

Following the scent at this odd hours, we were in front of a 24-hour bread store, still queuing, with one Afro-Cuban taking piping hot inch-long bread off the tray.

Cuban bread served 24-hour

There was only one kind of bread, and it only cost 10 CUP per baguette, which is about 40 cents in USD. It felt peculiar that bread is state-subsidized and almost a natural right like Cuba’s free education and healthcare. Plus, they are good — the bread was freshly made every day, everyone learns English at school, and Cuba boasts the lowest patient-to-doctor ratio in the world (which turned out to be another surplus). It is also admirable that the government does not discriminate against income, education level, or religion when it comes to these provisions. However, throughout my traveling in Cuba, what makes me sad is that the command economy might not be as responsive to people’s needs and the result is the limit to people’s standard of living. It is true that having been pampered by the comfort or even excess of capitalist economies, I can be biased in my judgment. Some desires are indeed created and needs are normative. And many Cubans, regardless of how shattered their clothes are, were joyful and friendly. However, there should be no arguing that greater quality, accessibility, and efficiency of essential goods and services would improve quality of life.

Regardless, we were just happy to get good bread at such a low cost when everything would be closed in Europe. Free from marketing influences and choices, we sank our teeth into the warm crusty loaf, and it was actually a slice of heaven.

(Special thanks to Jonathan Zimmermann for his valuable comments and for being a great partner in crime for this trip)

Printed with permission from Quanzhi Guo, view more blogs by Q.