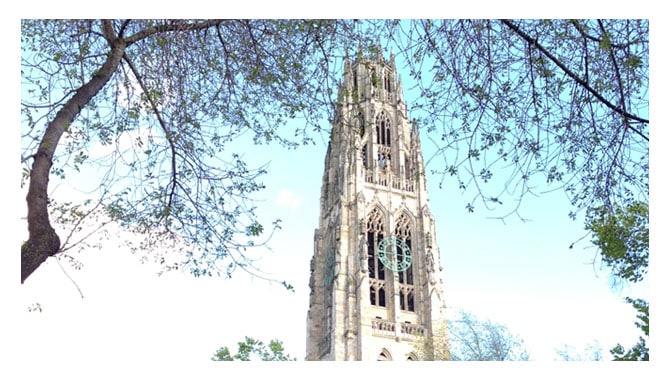

This year, the New England winter did not seem to end until the Yale underclassmen moved out. The good weather, of course, was reserved only for the commencement and the reunion weekends.

This year, the New England winter did not seem to end until the Yale underclassmen moved out. The good weather, of course, was reserved only for the commencement and the reunion weekends.

Besides warm temperatures, the three weeks that follow the end of the spring semester has always been a special time of the year. Personally, it felt great to be at school without the pressure of schoolwork. Instead, I was working five eight-hours shifts every week, for the third year in a row, preparing student dorm rooms for the parents and alumni who would stay there. In my spare time, I could finally check out random books from the library, visit Yale’s museums and galleries, catch up with friends and professors who are still around, and most important of all, spend time thinking about things that I’m often too busy to consider.

Standing afar from the stage during Yale’s commencement (the more than 10,000 seats in front of me on Yale’s Old Campus were all filled!) I felt a sense of anxiety, fearing that I wouldn’t be able to accomplish enough before my graduation next year. In the meantime, I would imagine sitting in the graduating seniors’ seats and anticipating a whole set of emotions that I might experience at graduation. Happiness? Sadness? Or just numbness? I won’t know until next year.

Soon after the commencement sends off the youngest alumni into the “real world,” the campus becomes eerily quiet for a few days. Then the older alumni, who graduated five, ten, fifteen and any multiple of five years up to sixty-five, would come back to attend their class reunions. In each of the classes are alumni who are very successful in their lives. Their achievements are evidence of the success of Yale’s education.

Among the things I thought about, amid the pomp and circumstance of commencement and the revelry of alumni reunions, I kept asking myself: “How is this possible?” How is it that a group of high school graduates, after spending four years at Yale, could go out in the world and achieve extraordinary things?

In other words, where does the real learning take place? This was the question that Bob Woodward, who taught my journalism seminar this past semester, asked my whole class to reflect upon. Woodward was one of the journalists who broke the Watergate scandal and is now the winner of two Pulitzer Prizes and the author of more than a dozen bestselling books. Like many alumni, he has his Yale education to thank for.

These are the questions that I can only partially guess. For me, real learning often seems to occur during the interactions I have with the people around me. Learning is not simply memorizing facts. It is also about battling ignorance and exchanging ideas.

But it’s difficult to say what exactly makes learning happen. In my view, each learning experience is a unique combination of time, place and people. The common variable of a Yale education in the past three centuries, of course, is Yale itself. More specifically, the real constant that buttresses Yale’s greatness is its philosophy of education.

This year I worked for the 65th and the 60th reunions. All the alumni were born during the Great Depression and have lived through roughly half of the U.S. history textbook. When they were at Yale in the late 40s and the 50s, all students were white males, and World War II was only recent history. The whole world seemed to be so different!

Yet the essence of a liberal education remains. In a handout by Yale’s class of 1956 alumnus and writer William H. H. Rees, titled “An Extraordinary Week in New Haven: Our First Week at Yale,” scenes from more than 60 years ago came alive on paper.

Of course, times have changed, but what remains is the belief in the liberal arts education. Rees quotes profusely from the opening speeches during Freshmen Orientation for the class of 1956.

“Education is designed to give students a sight into inner meanings and values, not merely a sight of the bare fact and the practical objectives of power, popularity and success…”

“The most important reason for the existence of a college is to give opportunity for conference—for the interchange of ideas, the debate which weeds out the false, which strengthens the true…”

Searching the speeches at my own freshmen orientation, I’m a bit surprised that the speakers did not directly address the meaning of the liberal arts education but instead focused on upward mobility and the diversity of ideas. But having spent three years at Yale, I can tell that those were the values in the 1952 speeches are not mere slogans. They look beyond the petty practicalities of education, breeding scholarship and nurturing leadership. These values, I suppose, are a big part of Yale’s living legacy.